Gareth O'Callaghan: Unanswered questions haunt Philip Cairns case decades later

On the afternoon of October 23, 1986, Philip Cairns disappeared as he walked from his home to his school, Coláiste Éanna, Ballyoran. Despite a lengthy Garda investigation into trying to establish his whereabouts, he has never been located.

Time is the investigator’s worst enemy, as I was reminded recently while listening to an interview with former FBI agent Kenneth Strange, who has played a major role in the inquiry into Annie McCarrick’s disappearance.

She vanished without trace from her Dublin apartment in March 1993. Her investigation was reclassified as a murder inquiry two years ago.

While it’s heartening to hope that gardaí might be closer to some form of closure in the case, I am also reminded that such an inquiry faces major problems in the absence of human remains.

McCarrick was one of eight young woman who disappeared in 1990s Ireland – a place where men who abused and murdered women were more often protected by institutions and influential groups who conspired to mislead and lie in order to shield these men’s identities and deflect from their crimes.

None of these cases has ever been solved – no bodies recovered, no suspects charged.

Convicted rapist Larry Murphy became the chief suspect in a number of the disappearances – despite other chief suspects who were known to at least three of the disappeared women, leading to the widespread belief that gardaí were dealing with a serial killer, which was later rubbished.

Then, out of the blue, came the news last Monday that gardaí have decided not to upgrade any further unsolved missing person cases to murder inquiries, including the case of 13-year-old teenager, Philip Cairns, who vanished while returning to school from his home in Rathfarnham, in Dublin, after lunch in October 1986.

I have spent a long time, since 2015, researching his disappearance. He will be missing 40 years next year. It’s difficult to imagine the toll it has taken on his family. Four decades on, every day must be a devastating reminder to them that his body is somewhere out there.

Pandemonium is the only way to describe the search in the days following Philip’s disappearance. Local gardaí didn't seem to have a notion how to deal with the abduction of a child in what is one of Dublin’s most celebrated upmarket suburbs, where “a small boy doesn’t just disappear”, as one local told me.

As the hours slipped away, so did the possibility of finding him alive.

Despite hundreds of leads from all over the country in the weeks and months that followed – some relevant, others bordering on tin-foil-hat theories - no one has ever come close to finding out what happened that autumn afternoon. Until nine years ago, when an unexpected suspect took centre stage.

In June 2016, gardaí announced that a woman had approached them the previous month, identifying the Dublin pirate radio operator and convicted paedophile Eamon Cooke as Philip’s killer. She told them that when she was nine years old in 1986, she had seen Cooke in his studios with Philip around the time he disappeared.

Gardaí said they had first met the woman in 2011, but she was unable to give a statement. What she told them then remains unclear.

Could Philip have known Cooke? Could a young girl – a victim of Cooke’s abuse – have seen Philip lying badly injured? It was even suggested that Cooke had promised Philip a visit to his radio station.

They were all possibilities in 1986, but what happened 30 years later turned the case against Cooke into a farce.

Cooke died in a Dublin hospice in June 2016 as a result of lung cancer, less than a week before gardaí broke their story. He was also suffering from end-stage Alzheimer’s – something the gardaí didn’t mention; yet in the lead-up to his death, detectives claimed he was able to tell them he had met Philip, and that the young boy had been in his car.

While aspects of the woman’s statement “were corroborated which opened new lines of enquiry,” gardaí said, “at this point in time these new lines of inquiry have not yielded positive results, however, the investigation is very much active and going.”

I worked with Eamon Cooke in 1979, unaware until years later of his abuse. He was a scruffy individual – a weird and eccentric loner. His sick perverted preference was young prepubescent children, mostly girls. In hindsight, he didn’t strike me as someone capable of killing a child.

Cooke was due in court on the Tuesday after Philip disappeared on charges of petrol bombing the home of one of his former DJs two years earlier, so is it likely he would have wanted to bring attention on himself by beating a child to death days before his court appearance.

His daughter – also a victim of his abuse – told me she didn’t believe he murdered Philip. So could he have been driven to the radio station that afternoon instead of returning to school?

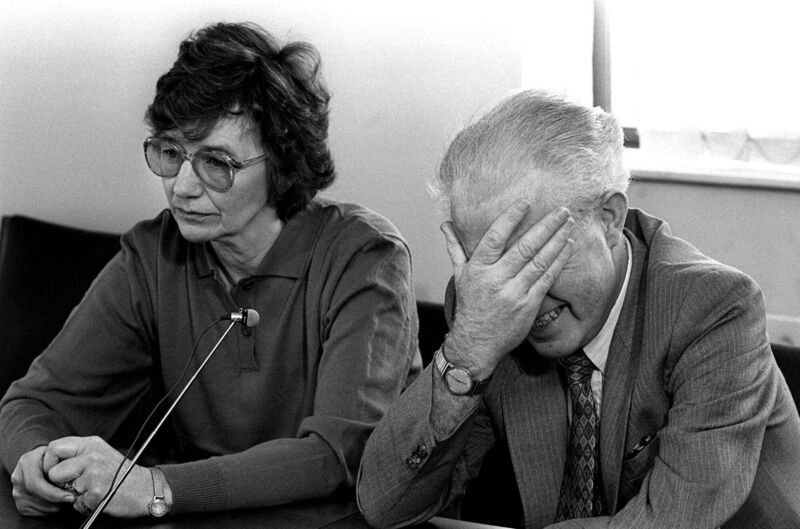

“I don’t think that Philip would have known or had anything to do with him [Cooke], to the music or whatever he was involved in,” Alice Cairns, Philip's mother, told RTÉ’s in June 2016.

Surely an account of an incident that has no witnesses from a woman who claimed she was nine years old at the time, told to detectives 30 years later, would have raised serious questions about the possibility of memory distortion. It appears it didn’t. They ran with it.

She decided to finally tell her story because she found out Cooke was dying. How? Why did all this information suddenly arrive into the public domain just days after he had died? It took barely a month for gardaí to announce that they believed they may have solved the mystery behind Philip’s disappearance.

Almost 10 years later, the absence of hard facts remains.

Could it be that gardaí have taken the decision not to upgrade Philip’s case to murder because the evidence pointing to Eamon Cooke that emerged suddenly and so unexpectedly following his death is implausible? Or could it be for an entirely different reason?

In August 2016, I met a man called who had met gardaí on two occasions, in 2010 and 2011, and gave an account relating to the back garden of a house on Dublin’s southside where he believed Philip’s remains may be buried. He explained he had been carrying out gardening work for the owner, who died in 2006, who knew the Cairns family.

One afternoon while this man was gardening, the owner, who was watching from an upstairs window, warned him not to dig in a specific corner of the garden after he struck a solid obstacle that felt like wood not far below the surface with a spade.

He later told this man he had done “some terrible things” during his life which haunted him. He didn’t elaborate.

Such was the credibility of this narrative, which included other highly sensitive and specific material, that I contacted gardaí, only to be told that the property would not be investigated, even though what they had received was first-hand information that I believe remains significant.

“The status of such missing person investigations is kept under regular review,” the Garda headquarters statement read last week, “and can be upgraded if new information and/or evidence comes to light that justifies its upgrading.” So was information given to gardaí in 2010 and 2011, and again in 2016, checked out, if only just to eliminate it?

A murdered child’s body lies in a shallow grave somewhere, his spirit calling out, pleading to be found. Last week’s decision by gardaí will surely come as yet another affront to a gentle loving mother whose heart has been breaking for her missing son for almost 40 years.