Ireland is becoming a better place to have a baby but there is still progress to be made in maternal care

Maternal care is improving, but mothers still report issues, especially postnatally, because nursing staff are ‘too stretched’

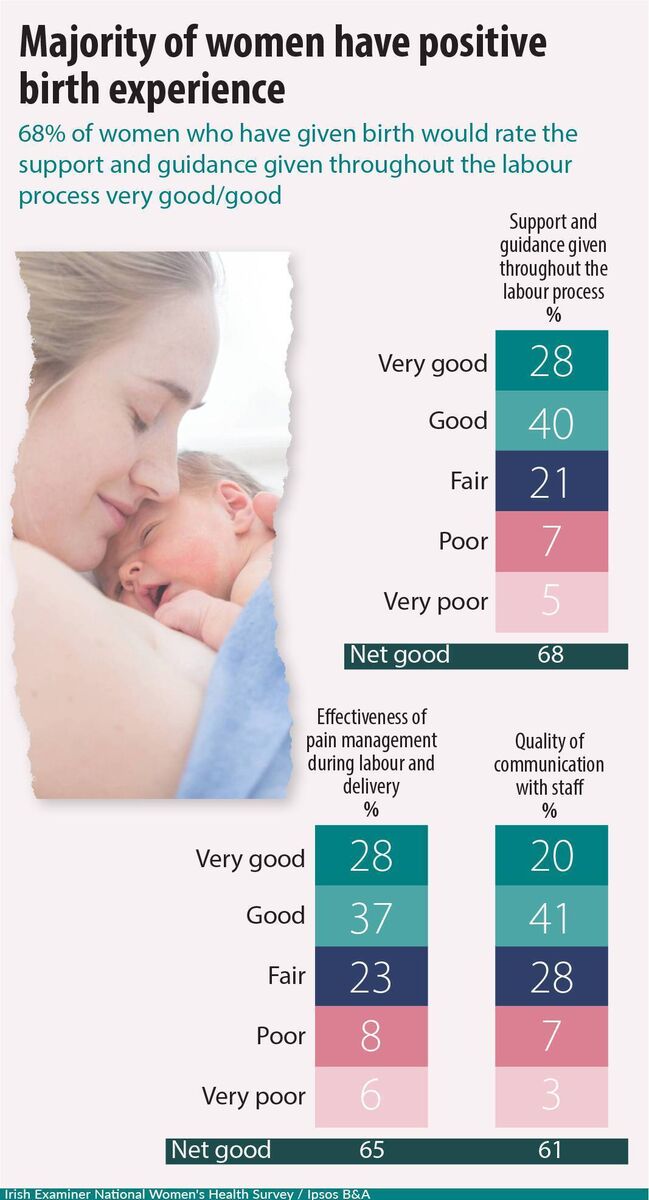

Ireland is becoming a better place to have a baby. That’s according to the National Women’s Health Survey, conducted by Ipsos B&A, in which women who have had multiple births report a gradual improvement in care over time.

However, there is still progress to be made. Some 41% of mothers said their first birth was difficult or complicated. Prenatally, 36% found healthcare professionals unwilling to consider alternative approaches to birth.

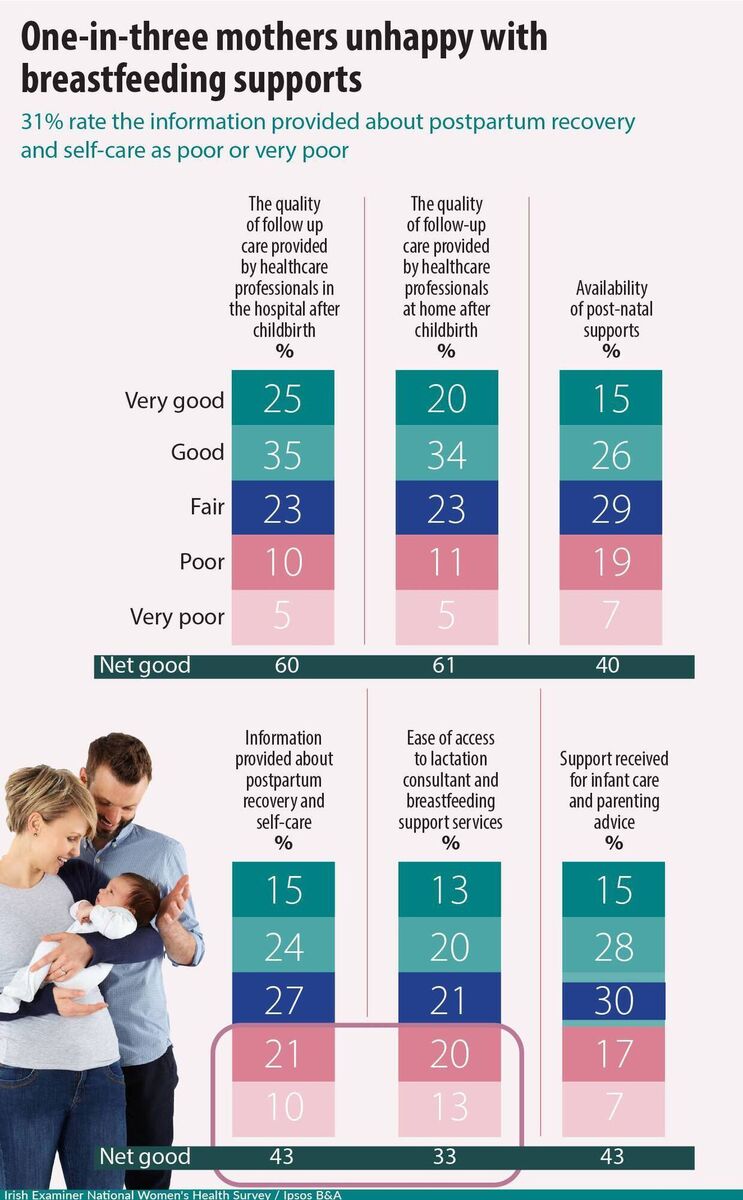

Dissatisfaction was highest with postnatal care. One in three cited problems accessing lactation consultants and breastfeeding supports.

Three in 10 feel there was a lack of information about postpartum recovery, and one in four said they didn’t get enough advice about looking after their baby.

Deirdre Daly, an associate professor of midwifery and director of the Centre for Maternity Care Research at Trinity College Dublin, believes the maternity service lets women down when it doesn’t give them adequate postnatal support: “Mothers need to learn how to keep themselves and their babies healthy and well, They need to be told what is and isn’t normal, so they can reach out for help, if needed. That’s how they get off to the best possible start.”

Tony Fitzpatrick, the Irish Nurses and Midwives Association’s (INMO) director of professional services, says that many of the problems within maternity services are caused by a lack of staffing.

This lack extends to postnatal care, where the shortage of public health nurses and general nurses results in inadequate care for mothers and babies after they leave hospital.

“With regard to postnatal care, the INMO has highlighted shortfalls in both public-health-nurse and community-registered, general-nurse staffing levels, as well as the numbers of midwives providing care in maternity hospitals,” he says.

“INMO members have reported they are striving to meet basic care needs for newborns and their mothers, but that they are far too stretched to give mothers the level of care they are trained to provide.”

What the INMO would like to see, he says, is “a maternity service that places women, babies, families, and midwives at the centre of care”.

Efforts are being made to create such a service. Daly sees the network of postnatal hubs that have opened around Ireland as a welcome development.

Run by midwives, they currently operate in Cork, Kerry, Carlow-Kilkenny, Sligo, and Portiuncula in Galway.

“Our research shows women often feel invisible in the maternity service, particularly postnatally, when the focus moves from mother to baby,” says Daly. “These hubs were set up as a pilot project in 2022 as a way of addressing that. For six weeks after birth and longer, if necessary, women can go to midwives with their questions and worries and midwives can identify and treat potential problems before they escalate.”

Dr Cliona Murphy, chair of the Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, adds that plans are under way to open an additional eight hubs throughout 2025 and 2026.

“Each will deliver accessible, woman-centred postnatal care to mothers and babies,” she says.

“They will provide multi-disciplinary support in local settings, with services such as breastfeeding support, birth reflections, and debriefing, wound care and more.”

There are other positive developments within the maternity service. Instead of a one-size-fits-all approach, women now have three care pathways to choose from, tailored to their individual clinical needs and preferences.

There has also been investment in education and training, with clinical practice guidelines being developed in subjects such as care for women using a birthing pool for labour and birth.

Chair of the Association for Improvements in Maternity Care Ireland (AIMS), Krysia Lynch, says there is much we could learn from other countries, citing Germany as an example: “Women there see the same midwife at all their appointments and build up a relationship of trust with them. We would benefit from that continuity of care in Ireland.”

She would also like us to emulate the French by including a postnatal pelvic check as standard: “Women’s pelvic health is so important for their general health and quality of life as they age.”

The key to increasing women’s satisfaction with the care they receive in the maternity system is ensuring that their voices are heard at all stages, according to Daly.

“Some 41% of first-time mothers find birth difficult or complicated,” she says. “Nobody thinks they should lower their expectations or anticipate complications. Instead, we should aim to exceed their expectations by consulting them and considering their needs prenatally, during birth, and after they have their baby.”

Stephanie Buckley is a 39-year-old mother of two from Tralee.

Her oldest is three, and she was well taken care of when she was pregnant with him: “My appointments and scans were great. I was listened to and cared for at all times.”

It was during labour that things started to veer away from what she expected. Buckley’s waters broke.

Labour started, but then stalled: “I was induced, and when he still didn’t come out, I had to have a C-section.”

She hoped for a different outcome with her second child, who is now four months old. “But it went the same way,” she says.

However, there was one big difference between the two experiences: The level of postnatal care: “After my first baby was born, the midwives were great, but they were so busy they couldn’t spend much time with me.”

She saw a lactation consultant and appreciated the visit from her public health nurse: “But I still had questions, particularly in relation to my C-section recovery, and would have liked more follow-up.”

She got this with her second baby, because, in the meantime, a HSE-run postnatal hub opened in Tralee. “It was everything I’d been looking for,” she says.

“At my first visit, I had a full debrief on the birth, was checked for postpartum depression, and the midwife looked at my wound. It was just about to get infected, but she caught it just in time.”

Buckley returned to the hub two or three more times after that to get her wound checked and ask more questions.

“I didn’t have to sit at home and wonder like I did with my first baby,” she says. “There were people I could talk to. That was missing the first time around, that extra layer of reassurance and support.”

Yvonne Harris, 39, has a three-year-old child and lives in Firhouse, Dublin.

Harris felt cared for throughout her pregnancy. “I was given good information and was always listened to,” she says. “It wasn’t until I went in to labour that things started to go wrong.”

She was 1.5cm dilated when she arrived at a busy labour ward. “Because I was in the early stages of labour and the ward was full, I was placed in a room at the end of the hall with women whose pregnancies were being monitored, but who weren’t in labour,” she says.

Her husband had to leave when evening came. “I’m quiet and don’t like to make a fuss, and because everyone was so busy, I wasn’t checked on much.”

When she was examined the next morning, she was fully dilated and was rushed to the delivery suite.

Her daughter was born by vacuum delivery, but Harris retained the placenta.

Attempts to remove it manually resulted in haemorrhaging, and she had to be operated upon.

She now wonders if her birth experience led to postnatal depression. “It kicked in when my daughter was six months old and I treated it with medication and counselling,” she says.

“Talking helped release the trauma I’d held on to from the birth.”

Looking back, she questions if her complications might have been avoided if her labour had been managed differently. “If I’d asked for help more or if there had been more staff to check on me, things might have been different.”

Ipsos B&A designed and implemented a research project for the involving a nationally representative sample of n=1,078 women over the age of 16 years.

The study was undertaken online with fieldwork conducted between April 30 and May 15, 2025.

The sample was quota controlled by age, socio-economic class, region and area of residence to reflect the known profile of women in Ireland based on the census of population and industry agreed guidelines.

Ipsos B&A has strict quality control measures in place to ensure robust and reliable findings; results based on the full sample carry a margin of error of +/-2.8%.

In other words, if the research was repeated identically results would be expected to lie within this range on 19 occasions out of 20.

A variety of aspects were assessed in relation to women’s health including fertility, birth, menopause, mental health, health behaviour, and alcohol consumption.